Making things move#

Most biomechanical investigations involve some sort of movement, so getting the model to move in the desired way is at the core of musculoskeletal modeling. The AnyBody Modeling System offers many and rather advanced methods to make this happen. This tutorial explains some of the common approaches.

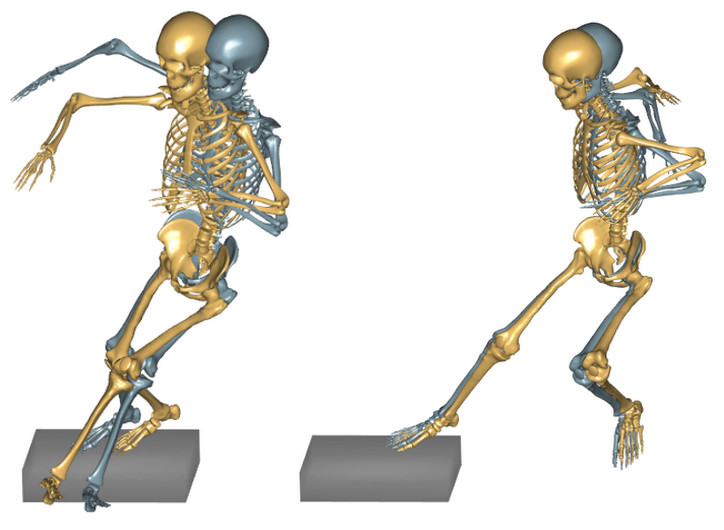

The figure above is a sequence of superimposed images illustrating a cutting movement. In the AnyBody Model View window, this will of course be an animation. The point of the figure, however, is that the movement is derived from a combination of joint articulations, and this introduces the concept of degrees-of-freedom, which we shall abbreviate in the following as DoF.

The number of DoFs in a model can be thought of as the number of different articulations the model has. The knee, for instance, is a hinge joint and can only flex or extend with respect to its predefined rotation axis, so this joint provides one DoF to the model. The hip joint, on the other hand, is a spherical joint, so it has three different rotations and therefore provides three DoFs to the model. Anatomically, these three DoFs might be called flexion/extension, abduction/adduction and internal/external rotation, but this is just one possible choice of terminology related to a selected coordinate system. We could choose infinitely many other angle definitions and sequences in the hip. Regardless of the choice there would always only be three independent possibilities, so the concept of DoF is rather general, and we shall explore it in a little more detail in the following on a very simple model.

In the following lessons we will look at simple and more advanced ways to drive a model. First, lesson 1 introduces an advanced gait model from AMMR of a walking human driven by motion capture data. The following lessons will explain how to build your own model to drive a simple pendulum using motion capture data, where exactly the same principles apply to much more complex models.